By Connor Newson

A few weeks back I fell in love… Yes, this is a love story. However it is not a story between two people, it is a story of a man and his discovery of the marvellous coconut. But like so many love stories there are moments when not everything is as sweet it seems. And for me that sourness came unexpectedly within a matters of days after first being exposed to the greatness of an Indian coconut.

At this point you might be why I’m writing about loving the coconut, or maybe why it has taken a person so long to even try a coconut. After all the world is not so big when they’re readily available in supermarkets all over the world. Nevertheless, love is subjective and these drupes of healthy goodness are usually packaged or served with a delicious and unhealthy layer of chocolate around the outside – yes, I’m referring to the Bounty bar. So of course I’ve tasted the artificial essence of coconut before, but somehow I can’t ever recall eating an actual coconut – especially when its fresh from the tree itself.

The romance began on a warm evening in a small ancient town called Maheshwar hidden within the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. Myself and two friends, Ellie and Connie, are taking a gentle stroll down the bank of the Narmada River, admiring the sun as it bounces off the water onto the Ahilyabai Temple that towers above the boats below. As is quite frequent in India, we stop at a street vendor for some tasty chai.

The fire is stoked, a pan is set, and a concoction of cardamom, black tea, ginger, masala, milk, and other spices are thrown inside. As the chai guy works his magic, Connie spots a horde of fury brown coconuts sat on a vendor’s table opposite ours. Already enlightened to the taste of coconuts, she wastes no time in approaching the vendor. Now I’ve only ever seen coconuts being smashed open by desperate shipwreck victims who are stranded on an isolated Island in the middle of the ocean… Hollywood. So I follow Connie, curious as to how she is going to take on this challenge.

Fortunately for her, the trader kindly begins to tear out the thick outer hair to reveal the significantly smaller shell underneath. Moving away from his station and placing a small glass on the ground where he is now crouched, he grabs the nut firmly in one hand and hurtles it at the concrete below. With one fell swoop a large crack appears which allows the liquid centre to spill into the glass. Then, wielding a 500g scale weight, he begins tapping at the shell to break off the pieces one by one, revealing the brilliant white sphere inside.

Immediately I am captivated by the raw method of fending for one’s self. I am caught in the crosshairs of curiosity, eager to taste the pure fruit that has just been revealed to me. But first, a sip of some coconut milk. With the heat of the Indian sun bearing down on me, the water runs down my throat fresher than the streams of Mount Everest. And now for the coconut itself. I take some from Connie and dig my teeth into the crunchy yet soft white chunk. I am hooked, and the initial attraction is obsessive.

We spend the next twenty minutes drinking chai and munching on coconutty goodness whilst watching the sun burst into shades of pink, red, orange, and yellow as it sets over the river ahead. The next morning we return, this time to open the shell ourselves to experience the arduous method first hand (simultaneously attracting a crowd of locals who were probably judging our inefficiency). The taste is as heavenly as the night before. I return once more before leaving for our next destination in India, uncertain on whether Omkareshwar would be as kind in fixing my new addiction. It was… But only temporarily.

Omkareshwar is 65km up the river with a huge temple built into the bank of its river. On our first evening we venture out to have dinner, treating ourselves (daily) to fresh and oily curry. Despite most places street stalls being closed this late in the evening, I manage to spot a friendly bunch of coconuts sitting in a basket outside a store on the way back to our hostel – one for me, and one for Connie. We cradle the precious things back to our rooms and devour them whilst reading our books.

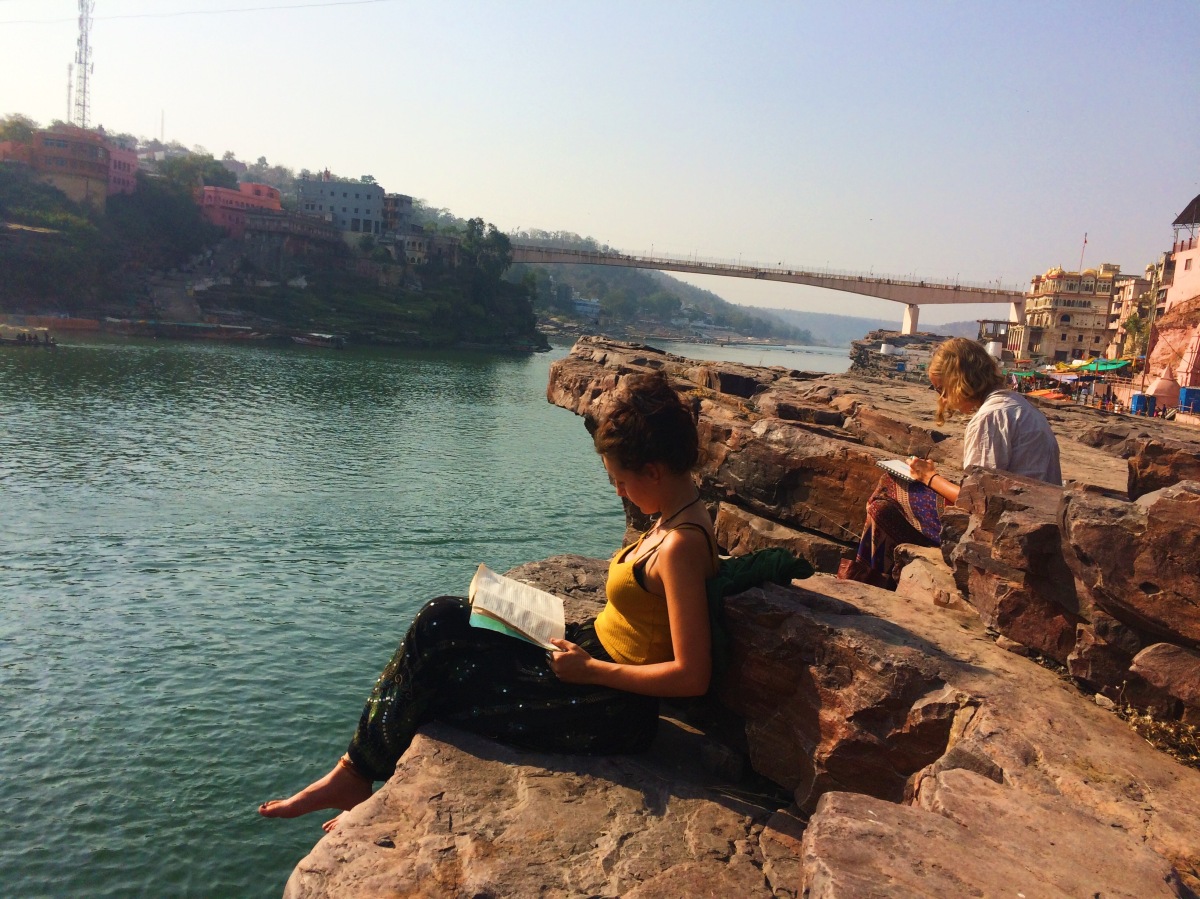

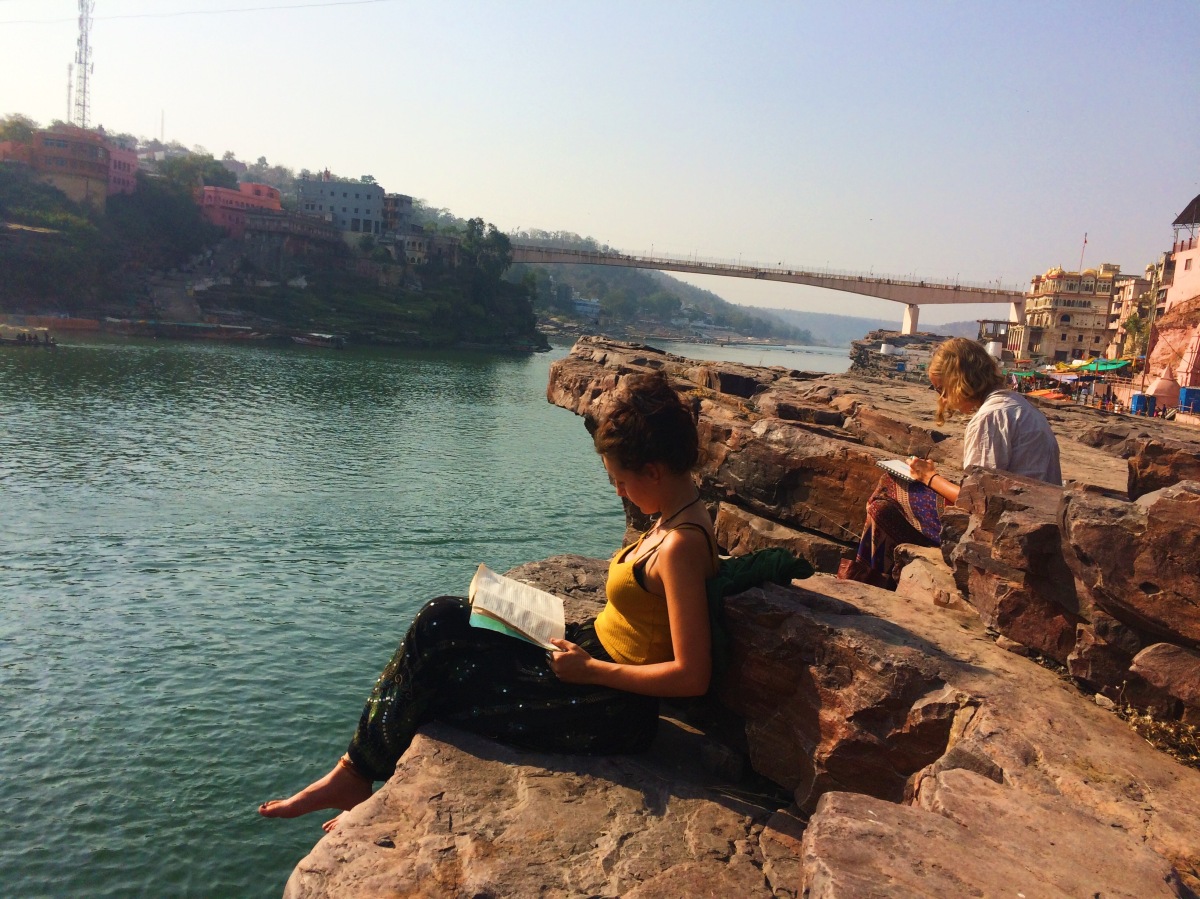

The next day we leave the hostel and go for a walk, little did I know that my walk would soon turn sour. We arrive at what seems to be a market square with about fifteen wooden structures pitched up in a long row. To my surprise, every single one of them has a basket of coconuts waiting to be plucked. I waste no time in my choosing, other than to shake a couple of nuts next to my ear to decide which one sounds bigger – the hairy exterior can be misleading. I make my choice and we continue walking until we find ourselves perched on the edge of an elevated rock by the river, away from any noisy crowds and with a beautiful wide view of the river running for miles into the distance.

As Ellie and Connie begin reading their books, I pull the coconut out from inside my bag and begin tearing out the straw like hair that covers the shell. My eagerness to taste the crunchy interior seems stronger with each one I consume. With the fury coating abandoned, I grip the nut tightly and force it down on to the rock at my feet. However nothing happens. I try once more, yet not even a hairline crack surfaces. I begin hammering down the nut hard against the ground until soon I notice my hand is slightly wet.

Finally there is a crack, but not where I have been hitting it against the rock. Upon closer inspection I notice a small hole at the top of the nut, and two other darkened circles that seem to have an unusual shade of mossy green. However, I continue to bring down the coconut with repetitive and heavy thuds against the rock until eventually it splits. All of a sudden my throat is wrenching at the stench unleashed. Thick white liquid leaks from the crevices as the shell falls apart, exposing a curdled creamy ball of mush that spills into my palm. Full of disgust and gagging at the repulsive smell emitting from my mouldy snack, I open my palm to let pseudo-coconut fall to the depths of the water like Jack from Titanic.

Feeling confused and rejected, I try to speculate on the cause for my mysteriously viscous coconut. Why would a coconut be so bad that its entire interior had managed to curdle? After a while we wander home, on the way passing the wooden shacks where just earlier I excitedly purchased the disappointing fruit. I avert my eyes and continue walking until I arrive at the store where I had bought a nut the evening before. I decide to confront my fears and buy one more coconut and take it back to the hostel, hoping the last was just a one-off.

Back at the hostel I ask for a hammer to assist the dissection. I place it on the floor firmly whilst simultaneously covering my nose with a sleeve. I raise the hammer above my head and prepare to slam it down onto the shell. Suddenly I hear a voice from behind.

“Are you going to eat that?!”, a German girl laughs.

“…Yes” I reply. “Shouldn’t I?”.

She senses my confusion and begins to explain her concern.

“Every day people buy these coconuts, and flowers, to lay in the river as gifts to the source of life that runs through the valley. After the coconut is gifted, locals climb into their boats and fish the coconuts back out of the water in order to sell again. In fact, once a year three-thousand coconuts are released into the river as gifts, and every single one of them is collected and put back into the system. I wouldn’t be surprised if that is a sour coconut”.

So there it is. The answer to my coconut’s deception. I had unwittingly purchased a coconut that had probably been circulating in and out of the river for months. Still, I have faith – or rather hope – that the one I hold in my hand right now is an exception like the one from last night. Before I can talk myself out of it I bring down the weight of the hammer onto the shell. Miraculously, the shell splits almost perfectly allowing the shell to be broken off with ease to reveal the pure white sphere underneath. Tonight I will once again enjoy the tasty snack. And so my love for a coconut persists. At least for tonight anyhow.